TL;DR

DraftKings is gambling while Kalshi is finance. Same dopamine, different laws.

A Depression-era crop statute and a Supreme Court case cracked the door, and capital blew it open.

Once you put money on an outcome, you stop analyzing and start defending.

On Sunday I watched the Super Bowl at a friend's apartment in the Marina. Just five of us, plus a baby and a dog. Very domestic. The wings I ordered were two hours late, though, so I spent most of the afternoon chastising the DoorDash AI support bot.

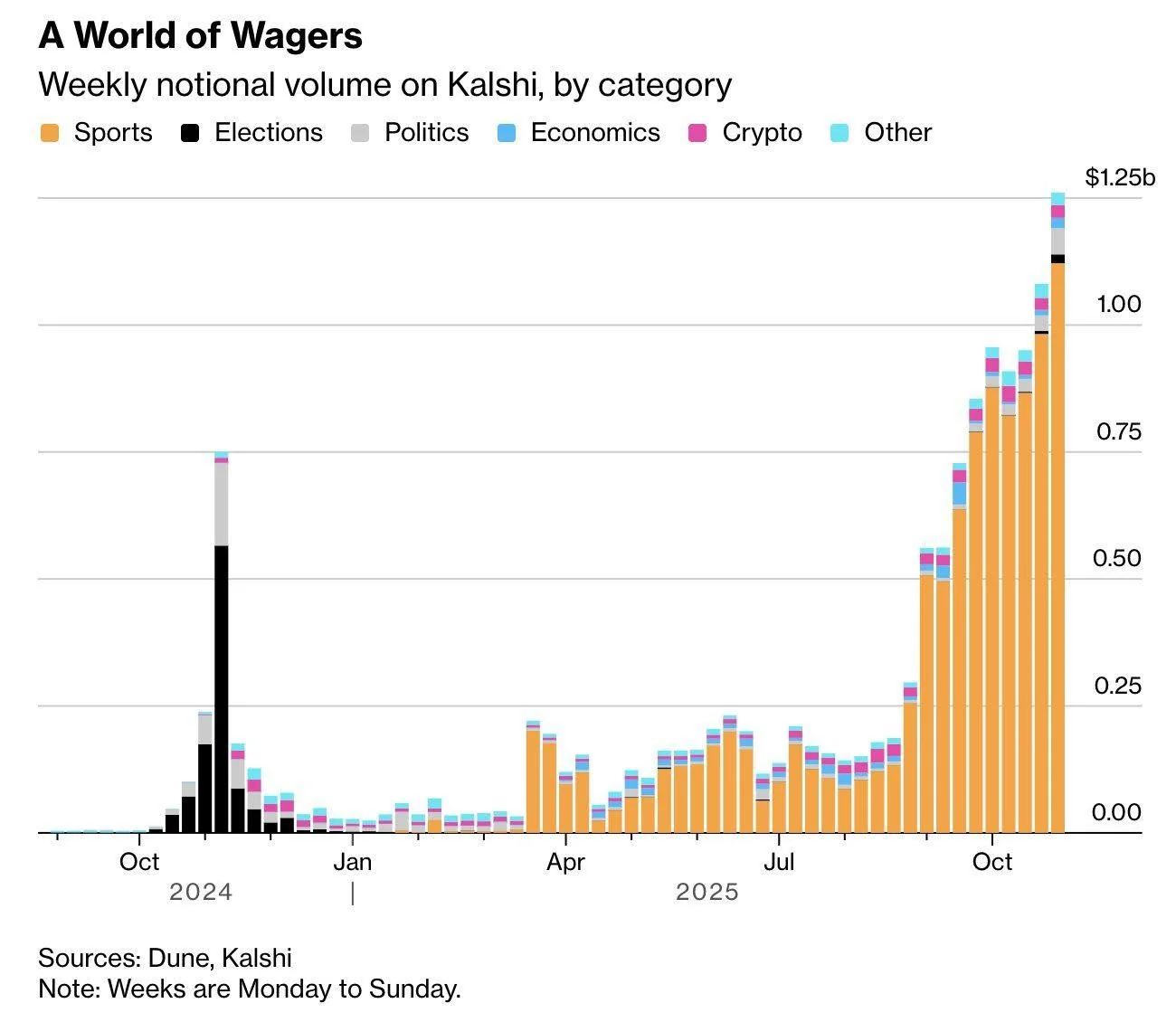

I don't bet on sports, I wouldn't know where to begin. I do, however, dabble in options trading and the occasional prediction market. And I'd be lying if I said the dopamine hit didn't activate something primal. Once a month I find myself refreshing Kalshi at 11pm to see if the probability of a Fed rate cut moved a tenth of a point. I then delete the app and vow never to return. My recidivism rate is 100%.

I build a gamification app for a living, and even I am not immune.

During the first quarter of the Super Bowl, a DraftKings ad ran. Then BetMGM… then FanDuel… then Fanatics. Four sports betting apps, four glossy spots. The Super Bowl has become a gambling infomercial with a football game attached.

We remarked on it between plays. You can bet on the game’s outcome, the length of the national anthem, whether the coin toss lands heads, or what song Bad Bunny opens with at halftime. The prop bets have gotten so granular it feels outright dystopian.

Most people lump all of these apps together. DraftKings and Kalshi, they’re gambling apps. You pick an outcome, put money on it, wait.

I did too. Turns out DraftKings and Kalshi exist in completely different legal universes. One is regulated as gambling under state law. The other is regulated as a financial instrument under federal commodities law. The NFL welcomed four sportsbooks as official advertising partners this year, but prediction markets have been blocked from advertising at the big game.

Same behavior, wildly different legal plumbing.

I spent a lot of Sunday evening with ChatGPT trying to figure out how we got here. The answer involves a Supreme Court case, a statute written for Depression-era farmers, and a jurisdictional fight that will probably define how America regulates risk for the next generation.

How Sports Betting Went Mainstream

For most of my life, sports betting was illegal outside Nevada. A 1992 federal law called PASPA prohibited states from authorizing it.

In 2018, the Supreme Court struck PASPA down in Murphy v. NCAA. The reasoning: Congress can't commandeer state legislatures by preventing them from changing their own laws. If New Jersey wants to legalize sports betting, New Jersey can.

After Murphy, the map filled in fast. New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Arizona. Each state built its own licensing structure, tax rates, and compliance rules. DraftKings and FanDuel applied for state licenses. They pay state taxes and comply with age verification and self-exclusion programs.

Meanwhile, prediction markets took a very different path.

From Corn to Kalshi

Prediction markets didn't grow up under gambling laws. They were born under derivatives law, specifically the Commodity Exchange Act, a statute written in the 1930s to regulate farmers hedging crop prices.

The CEA is overseen by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, a federal agency most people have never heard of. Under the CEA, exchanges can list "event contracts" as long as they meet certain criteria and avoid prohibited categories like terrorism and war.

Kalshi became the first CFTC-regulated exchange built specifically around event contracts. Their argument: these are financial instruments traded on a federally regulated exchange.

These are derivatives, not bets!

That distinction is everything.

If a contract is a CFTC-regulated derivative, federal law preempts state law. The exchange can operate across state lines without fifty separate gambling licenses. DraftKings needs a regulator in every state, but Kalshi just needs one federal agency to say “yes”.

When the derivatives loophole met sports betting, the floodgates opened.

Nobody who wrote the Commodity Exchange Act in 1936 imagined someone would use it to let retail investors trade election outcomes from their phones during a football game. But laws create boundaries, and entrepreneurs find the gaps.

I've seen this before. My startup operates in cannabis, an industry built entirely inside a regulatory gray zone. I watched the hemp loophole create a $28 billion industry and then watched Congress kill it overnight through a budget rider. The pattern is always the same: ambiguity, exploitation, scale, then a fight about who gets to regulate what.

Skin in the Game

All of this legal architecture adds up to something bigger than a regulatory turf war.

Ten years ago, if you thought the Fed would cut rates, you told your friend at dinner and maybe moved some money into bonds. You held a belief, and beliefs are flexible. You update them when new information arrives because there's limited cost to changing your mind.

Now you open Kalshi, buy a contract, and watch the probability update every thirty seconds. You hold a position, and positions are sticky. They anchor you. There's money on the line, which means there's ego on the line, which means new information gets filtered through a question that has nothing to do with truth: does this help or hurt my bet?

I notice it in myself. When I check Kalshi, I'm not thinking about probability. I'm scanning for signals that confirm the direction I already bought into. Dovish Fed language feels like validation while hawkish data feels like noise to be dismissed. I'm not forecasting, I'm defending an investment.

This is a cognitive shift, and I think it's more interesting than the addiction angle everyone else is writing about. "Gambling apps exploit dopamine" is true and also obvious. The subtler thing is what happens to your thinking once you've got skin in the game. The wager becomes a lens that distorts.

Think about how sports betting changes the experience of watching a game. You stop seeing the game, you just see your bet. Every play becomes evidence for or against your position. The thing itself disappears behind the wager.

I think something similar is happening to how we relate to the future more broadly. We've built infrastructure that lets millions of people convert beliefs into positions on everything: elections, interest rates, geopolitical events. And people with positions behave differently than people with beliefs. They dig in and look for confirming evidence. They need the future to go their way because they've bought a contract that pays out if it does.

I’ve written before about how Americans inhabit incompatible realities. Tradable uncertainty might accelerate that. People who have money riding on an outcome don't just consume different media, they need different facts.

Having skin in the game changes what you're willing to accept as true.

Nobody’s Problem

In December I predicted that gambling will become a public health crisis. Half of young men in America already have a sports betting account. One in five gambling addicts have attempted suicide. The dopamine architecture is identical to social media: frictionless deposits, complicated withdrawals, push notifications when you haven't bet in a while.

State gaming commissions regulate betting as a vice, governed by age limits, self-exclusion databases, responsible gaming messaging. Consumer protection is built into the framework.

Since 2018, searches for gambling addiction have run significantly above projected baseline. Via UC San Diego

The CFTC regulates markets as financial instruments. Capital adequacy, anti-manipulation safeguards, orderly settlement. The framework was built for institutions hedging interest rate risk. It was not designed for millions of retail participants trading emotionally charged outcomes from their couches at 2am because they saw a viral TikTok.

Prediction markets use the sportsbook playbook but operate under a framework with none of the consumer guardrails. Nobody has figured out who's supposed to close that gap. And in the meantime, the legal ambiguity is generating enormous returns for the platforms occupying it.

Uncertainty for Sale

The Super Bowl ads were an announcement: the legal architecture required to sell the future as a consumer product has matured enough to compete for the most expensive advertising real estate on Earth.

A Supreme Court decision cracked the door for sportsbooks and a depression-era farming statute did the same for prediction markets. Capital blew both doors open.

We used to sit with uncertainty. We’d argue about it over dinner and hold beliefs loosely enough to update them when the world surprised us. But today, we buy positions. And positions have a way of calcifying into identities.

I keep deleting Kalshi and reinstalling it. I tell myself it's research, but I know what's actually happening: the app has turned my curiosity about the future into a position I need to defend. And every time I refresh, I'm a little less interested in what's true and a little more interested in whether my trade is going to print.

Once you buy a position on the future, you stop thinking about it clearly. You just double down.

Up and to the right.