TL;DR

Infinite content has made curation the scarcest resource in entertainment.

The Warner Bros. Discovery bidding war is a $100 billion bet on institutional credibility.

We celebrated the death of gatekeepers, and in the process made the survivors priceless.

I love TV.

I've organized significant chunks of my social life around television. In high school, I'd stay up way too late watching Lost and then spend the next day at school analyzing what the smoke monster meant with anyone who would listen. Throughout college, Sunday nights were sacred. P-sets and midterms be damned, Game of Thrones was what mattered. Nobody was on their phone. We were locked in.

Succession, Euphoria, True Detective, House of Cards, Black Mirror… I love it all. I've ended evenings early to make it home for a finale. I once cancelled a date altogether because it conflicted with a season premiere of Curb Your Enthusiasm. I still think I made the right call.

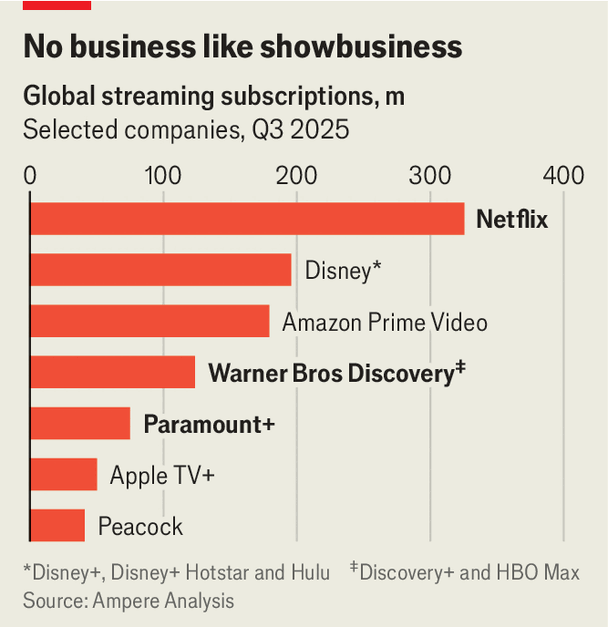

Netflix’s early dominance rewired television’s economics around scale and infinite supply. Via The Economist

Television, for me, has always been communal. The shows mattered, obviously. But what mattered more was the shared experience of watching them at the same time as everyone else, then spending the next week dissecting theories offered by strangers on Reddit.

That experience is dying, and lately I’ve been thinking the culprit isn't what most people assume.

The conventional wisdom blames fragmentation. Too many streaming services, too much content, audiences splintered into micro-niches. But fragmentation is a symptom. The deeper problem is that trust has become the scarcest resource in the attention economy.

When I was watching Lost, television operated on scarcity. Limited channels, fixed time slots. If you missed an episode, you waited until it aired again. That constraint forced attention to converge.

More importantly, “This is on HBO" solved the discovery problem instantly. The brand was a signal. It meant: smart people are watching this. If you care about prestige television, tune in.

Now, "This is on Netflix" means something just… exists. Somewhere in a library of 10,000 other titles.

Content and Condiments

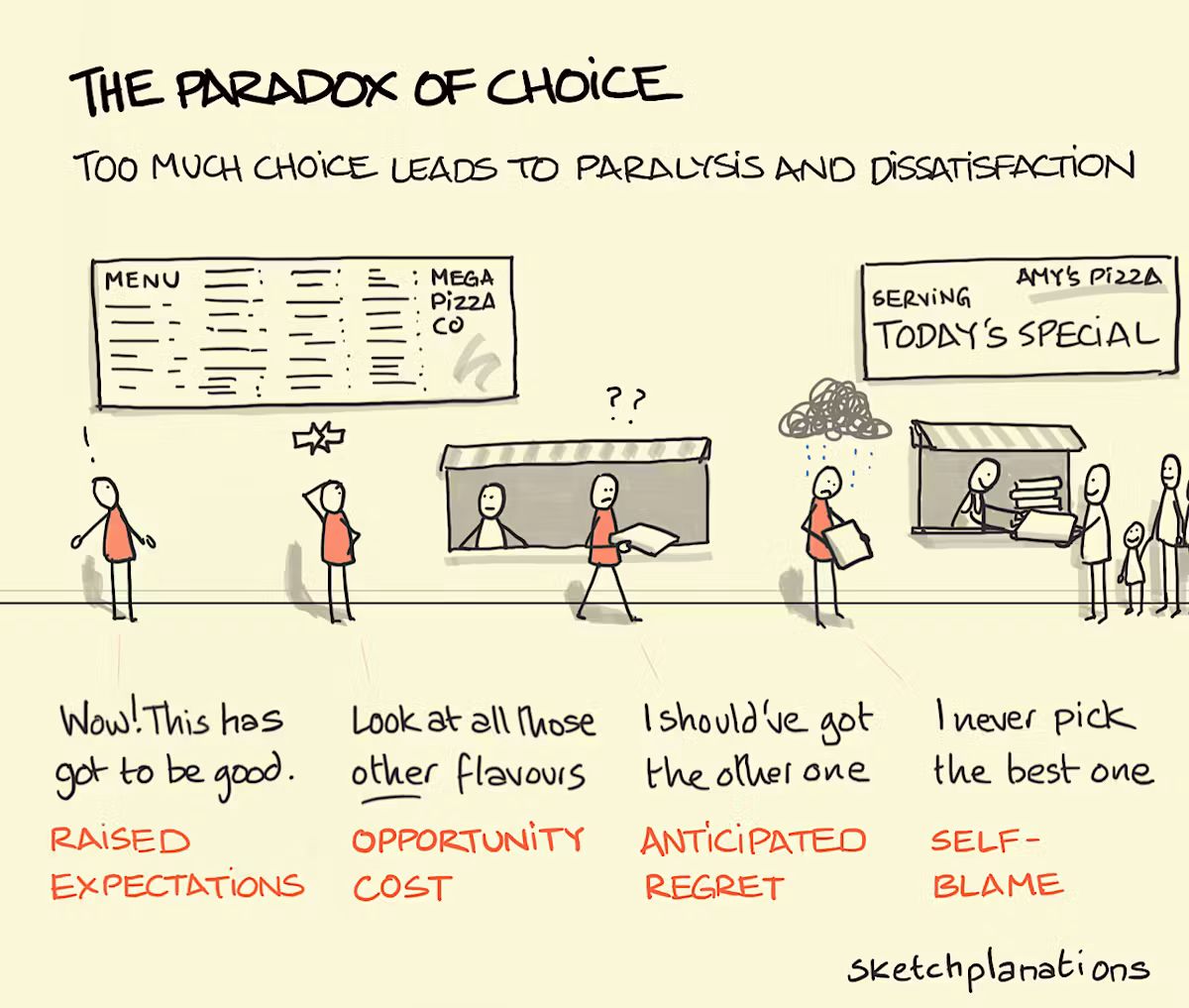

There's a famous study from 2000 that I (not kidding) think about constantly.

Psychologists set up a jam tasting booth at a California grocery store. Some days they displayed 24 varieties. Other days, just 6.

The big display drew crowds. People loved looking at all that jam. But only 3% actually bought anything.

The small display attracted fewer browsers, but 30% of them walked away with a jar.

More choice led to less action. Moreover, the people who bought from the 24-jar display were also significantly less satisfied with their purchase than those who chose from 6. Unlimited options produced paralysis and regret.

Costco, Williams-Sonoma, and countless other specialty retailers have built empires on this principle. Walk into any Costco, for example, and you'll find two types of peanut butter. At Williams-Sonoma, you will find just a single toaster, selected by someone with better taste than yours. The model correctly assumes consumers don't actually want more options; consumers want confidence in the options available.

The Paradox of Choice by Barry Schwartz is an AWESOME read for anyone building or marketing a product. Via Sketchplanations

Television used to work like Costco. A handful of networks, a handful of time slots, institutional brands that staked their reputations on what they aired. The scarcity was frustrating, but it came with a gift: someone else had already done the filtering. You could trust that whatever made it through was probably worth your time.

Streaming promised liberation from those constraints. Suddenly everything was available all the time. No schedules, no appointment viewing. The algorithm would serve you an optimized feed based on your viewing history. Perfect personalization and infinite choice.

What nobody anticipated was how exhausting infinite choice would become.

Netflix's recommendation engine is technically sophisticated. It knows what I've watched, what I've paused, what I've abandoned. It can predict what I might like. But it cannot tell me what matters. It cannot replicate the feeling of knowing that everyone I'll talk to tomorrow watched the same episode I did. It cannot manufacture urgency or social consequence.

And as a result, so many of us spend twenty minutes scrolling before giving up and throwing on The Office.

Bidding War

Warner Bros. Discovery is currently the subject of a bidding war. Netflix and Paramount are fighting over it, along with their respective private equity and Middle East backers. The latest bid exceeds $100 billion.

The conventional explanation is that everyone wants the IP. Warner owns HBO, DC Comics, Harry Potter, Lord of the Rings. Franchises they will mine for sequels and theme park rides until the heat death of the universe.

But IP alone doesn't explain the premium.

Disney owns Star Wars and Marvel, arguably the two most valuable entertainment properties ever created. They're still struggling. The Acolyte cost $180 million and evaporated from cultural memory within weeks. Secret Invasion had Samuel L. Jackson and landed with a thud.

Disney has the franchises, but what they've lost is the institutional authority to make any particular release feel essential. They produce so much Marvel and Star Wars content that each new entry dilutes the signal. When everything is a must-watch, nothing is.

HBO maintained the opposite posture for fifty years. They employed people whose entire job was to say no. To filter, to curate, and to protect the brand's credibility by passing on 95% of pitches so that audiences would trust the 5% that made it through.

That function seemed antiquated five years ago, but it seems now it's becoming the entire game.

The Warner bidding war makes more sense through this lens. Netflix and Paramount are trying to acquire an institution that still knows how to make people believe something matters.

A Trust Economy

The economics of attention have inverted.

When distribution was scarce (limited shelf space, limited broadcast slots, limited theater screens), the valuable skill was getting your content in front of people. Marketing, relationships, access.

When distribution became infinite (streaming, social media, algorithmic feeds), the constraint shifted. Getting content in front of people is trivially easy. Making people trust that it's worth their finite attention is almost impossible.

I made a short film a few months ago using AI tools (linked below in case you missed it 😉). I wrote the script with ChatGPT, generated a synthetic voice in ElevenLabs, created every shot using Google's Veo, and cut it together in iMovie. It took about twelve hours and cost ~$150 in AI subscriptions.

Five years ago, that project would have required a crew, equipment rentals, post-production facilities. Tens of thousands of dollars and weeks of coordination.

The technology worked. But when I published the film, it disappeared into the void within days. I can make almost anything now. What I cannot manufacture is any apparatus to signal that this particular thing deserves five minutes of someone's attention. No institutional stamp, no collective experience, and no trust.

HBO could greenlight a documentary about paint drying and a meaningful audience would tune in, because fifty years of curation trained them to believe HBO doesn't waste their time. I can produce professional-looking content from my laptop and struggle to get my own friends to click play.

The flood of AI-generated content will make this asymmetry more extreme. When creation costs approach zero, the only remaining question becomes: how do I know this is worth my time?

Algorithms can't answer that question. They optimize for engagement, which is a measure of addiction. Trust is something else entirely. Trust is the accumulated credibility of an institution that has repeatedly demonstrated good judgment over decades.

Death by Optimization

I predict that whoever buys Warner will probably destroy what they're paying for.

The machinery that makes HBO valuable (the patience, the restraint, the willingness to pass on most pitches) contradicts everything about how streaming platforms operate. Netflix needs volume to feed their algorithm. They need content velocity to justify infrastructure costs and keep subscribers from churning.

Netflix’s recommendation system requires an ever-growing supply of IP to sustain engagement. Via What’s On Netflix

HBO's model depends on the opposite. Release fewer things and make each one feel like an event. Train audiences to trust that if you're putting something out, it's worth their attention.

Those two systems don't combine, and one will consume the other.

I expect someone will acquire the HBO brand, strip out the curation layer to "optimize" output, flood the platform with content to compete on volume, and wonder three years later why the magic disappeared.

The magic was never the IP. The magic was the institutional willingness to leave money on the table by saying no. That discipline is precisely what a volume-hungry acquirer will find intolerable.

The Gatekeepers’ Revenge

We spent twenty years celebrating the death of gatekeepers. It turns out, we were just making the surviving ones more valuable.

Maybe a few platforms eventually figure out that restraint is the product. Deliberately limited output, premium pricing, positioning themselves as the anti-algorithm for people exhausted by infinite scroll. HBO's model, but self-consciously marketed as a luxury good.

Or maybe we just keep fragmenting. Infinite creation, algorithmic curation, and nothing that feels culturally significant. The collective experience I had watching Lost and Game of Thrones becomes a relic of constraints that no longer exist.

Either way, something has shifted. The technology that was supposed to democratize storytelling has made institutional trust more concentrated than ever.

I can make a hundred more films now, that barrier is gone.

But making something people actually care about requires something I can't build alone: a brand that has earned trust over decades, one rejection at a time.

Up and to the right.